One of the most famous ancient Greek tragedies is the story of Medea, the exotic foreigner who marries Jason (of Jason and the Argonauts fame). They adventure together, calling upon her skills as a sorceress to settle his family injustices. They eventually end up in Corinth, where Medea is forever the outsider and Jason swiftly becomes part of the establishment with his engagement to the King’s daughter.

Medea is rejected and humiliated. As a woman and a foreigner, she has little recourse. She decides on the plan that will hurt Jason the most, and she takes actions that have stunned and shocked audiences for two and a half thousand years.

Maria Callas plays Medea in the 1969 film.

MEDEA: But he, with God’s help, will pay the price.

He will never see alive again the sons

he had by me;

CHORUS: But can you bring yourself to kill your own sons, madam?

MEDEA: It is the way to hurt my husband most.

(Euripides, Medea 781-783; 795-6)

Medea sends her sons to the princess with a present of a poisoned robe. When they come home, she wavers, but goes through with her plan, and she kills them as the ultimate punishment and revenge against Jason. The princess dies grotesquely when she puts on the robe, as does the King when he embraces her dead body. Jason comes back to take the children away from her, only to discover she has killed them.

MEDEA: I wasn’t going to let you show dishonour to my bed

and live a life of pleasure, mocking me –

(Euripides, Medea 1333-4)

Ever since it was first performed in Athens in 431BC, this has been one of the most discussed and debated plays in literary history. One of the questions people often ask is how realistic is it that a woman could do something so monstrous? What does the fact that Medea is able to commit such a crime say about her – does the fact that she is a sorceress and part divine somehow make her removed from ordinary people?

But every so often a terrible event reminds us that this is not just an academic discussion, but that Greek tragedy tells stories that are still current today.

I was reminded of Medea by reading the news reports of a woman who is on trial for killing her two children. The prosecution is alleging that she killed them to punish her partner, their father. The prosecutor said,

“By any normal standards of human decency it is almost impossible to conceive of using the children as the ultimate pawns by killing them to truly wreak revenge on their father for having rejected the defendant and taken up with someone else,”

But of course that is why Medea chooses it. At the end of the play, she rides off in a chariot given to her by the Sun god, her grandfather.

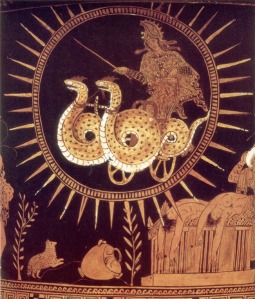

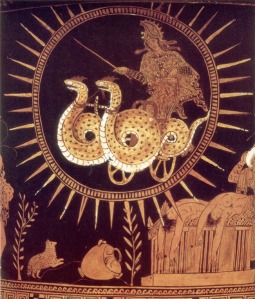

An ancient vase painting of Medea escaping in her chariot. The bodies of her children are in the bottom right corner.

She has already arranged asylum in Athens and she flies away, knowing she will escape punishment. Jason is left alone on stage. His children are dead. His fiancee and her father, the king of Corinth are dead. Medea’s revenge is complete. As Medea flies off, the audience has to ask what is left for her? She has successfully destroyed Jason’s life, but what is there now for her? They were her children too.

Greek tragedy forces us to ask these big questions and Medea is a play that poses some very big questions…

~

Euripides lived in Athens, Greece, between about 490/480 and 407/6 BC. He was the latest of the three famous Athenian tragedians, (the other two were Aeschylus and Sophocles) and we have 18 of his plays surviving. Medea was first performed in 431 BC.

Read more about Medea and her life on the Greek Mythology Link an excellent collection of biographies of mythological figures, written by Carlos Parada.

The Cambridge Translations from Greek Drama series has an excellent edition of Medea with an introduction to Greek theatre, a commentary with lots of explanations and things to think about and a lovely powerful but sparse translation of the play.

The consensus has been that the most western part of the empire was Exeter, which was a Romano-British town called Isca Dumnoniorum, the principal town of the Dumnonii tribe. They were a tribe hostile to the Roman invasion and the subsequent programme of Romanisation, and it was believed that they managed to hold on to their own territory and so prevented the Romans from moving further west.

The consensus has been that the most western part of the empire was Exeter, which was a Romano-British town called Isca Dumnoniorum, the principal town of the Dumnonii tribe. They were a tribe hostile to the Roman invasion and the subsequent programme of Romanisation, and it was believed that they managed to hold on to their own territory and so prevented the Romans from moving further west.